It’s not worth it

Our family is on a desperate quest to warn parents of the tragic consequences of collision sports’ repetitive hits to the head.

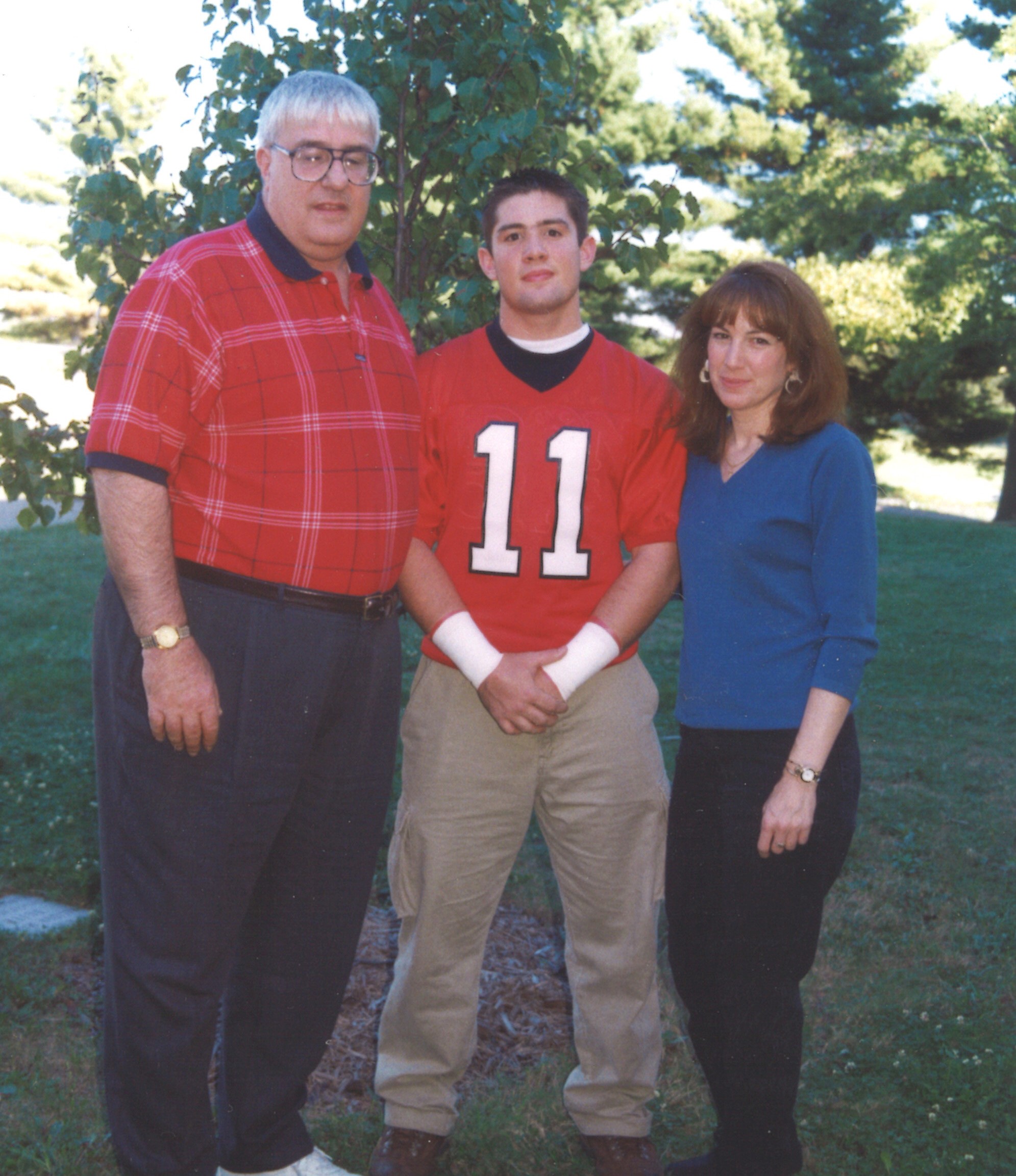

Since our son Patrick Risha died by suicide at the age of 32 after his brain was destroyed by Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), we have worked relentlessly to bring attention to the extreme danger of repetitive hits to the head. From ad campaigns and literature drops to speaking engagements all over the country, we have raised the alarm, always hoping to convince parents, coaches and athletic directors of the dangers of this deadly — and wholly preventable — disease.

A brain, and a life, destroyed

We thought parents would be anxious to learn more and would duly spread the word, and that children would be immediately spared. Sadly, in almost 10 years of advocacy, we have seen only a slight drop in youth tackle football participation.

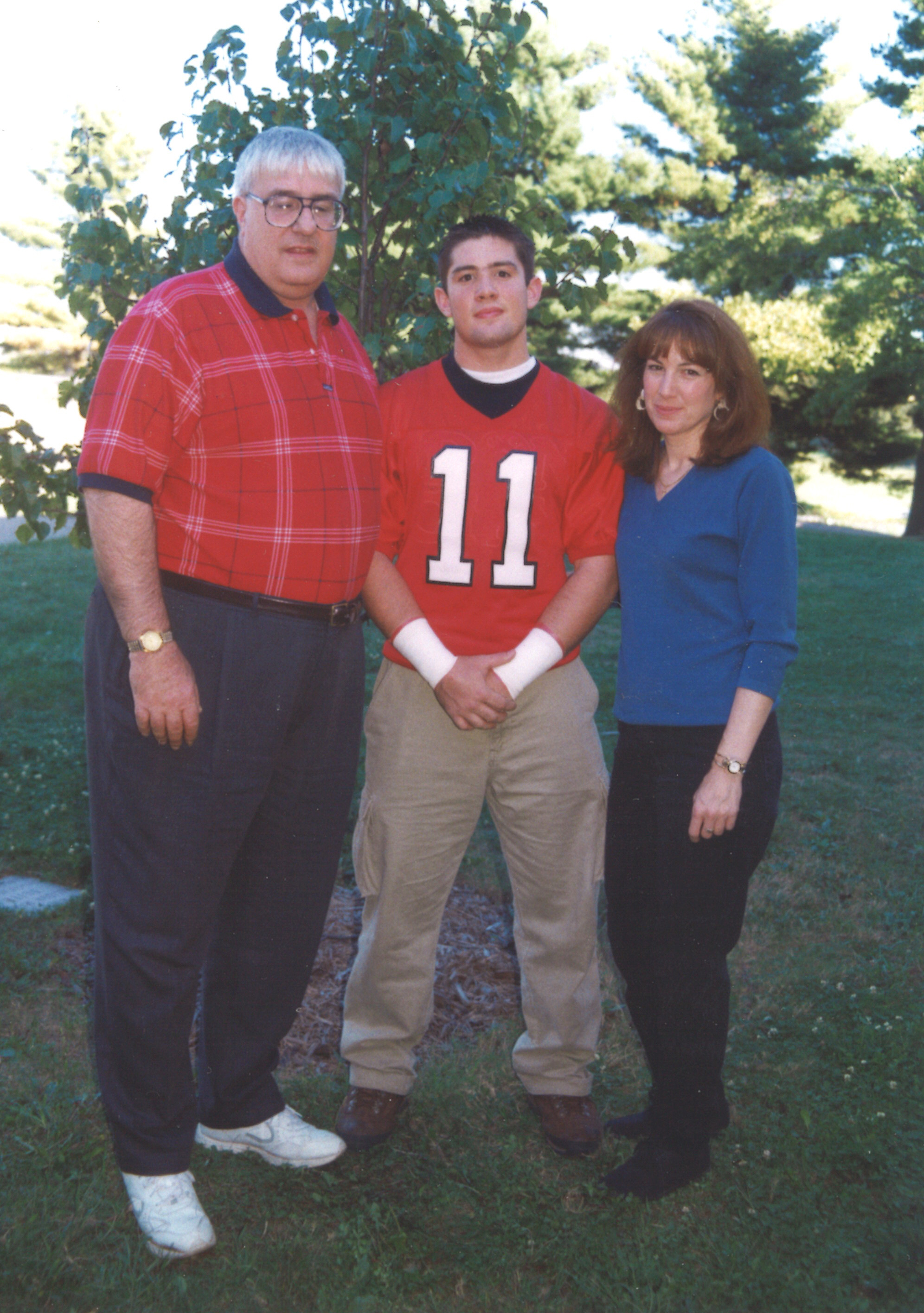

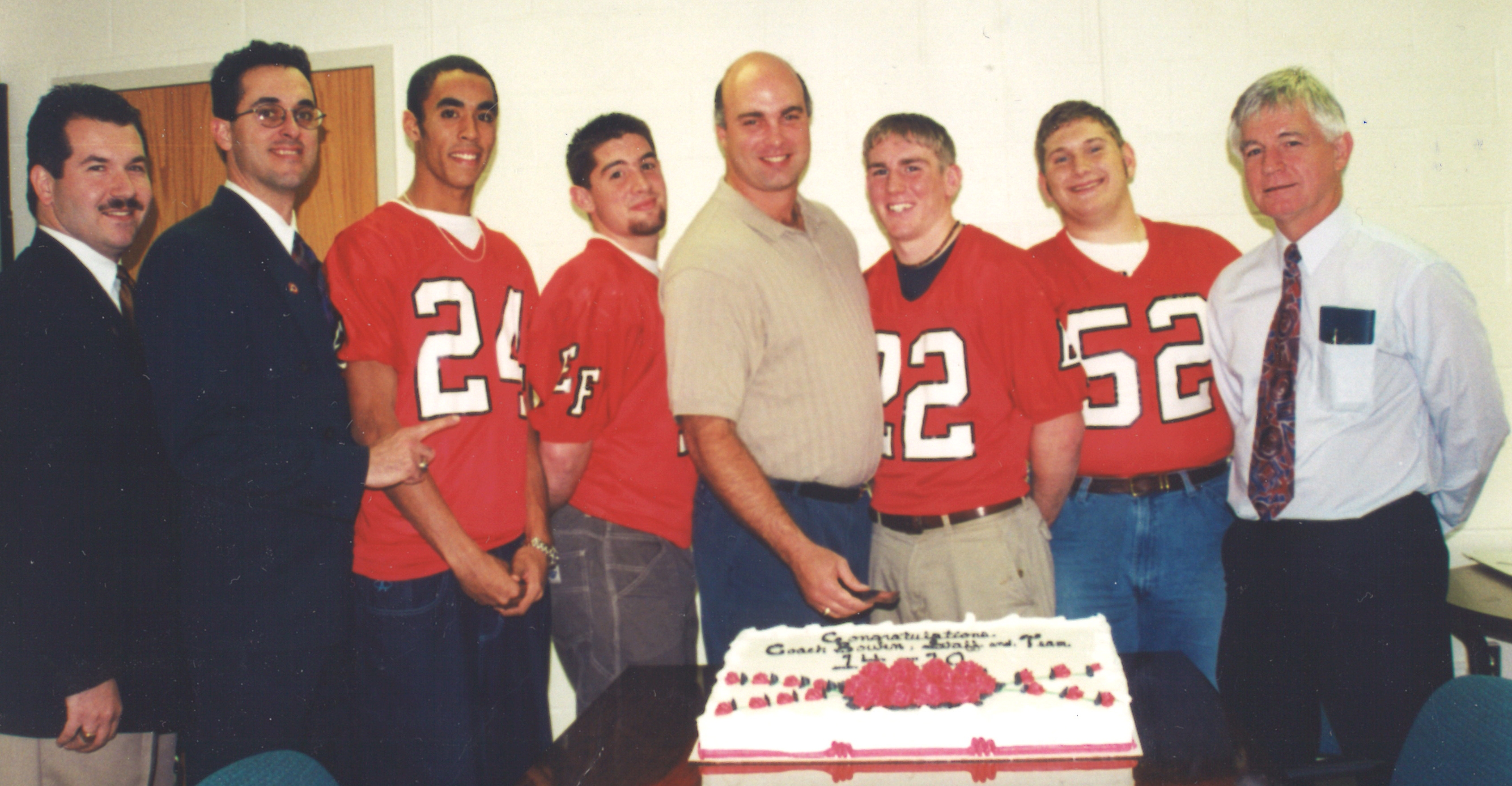

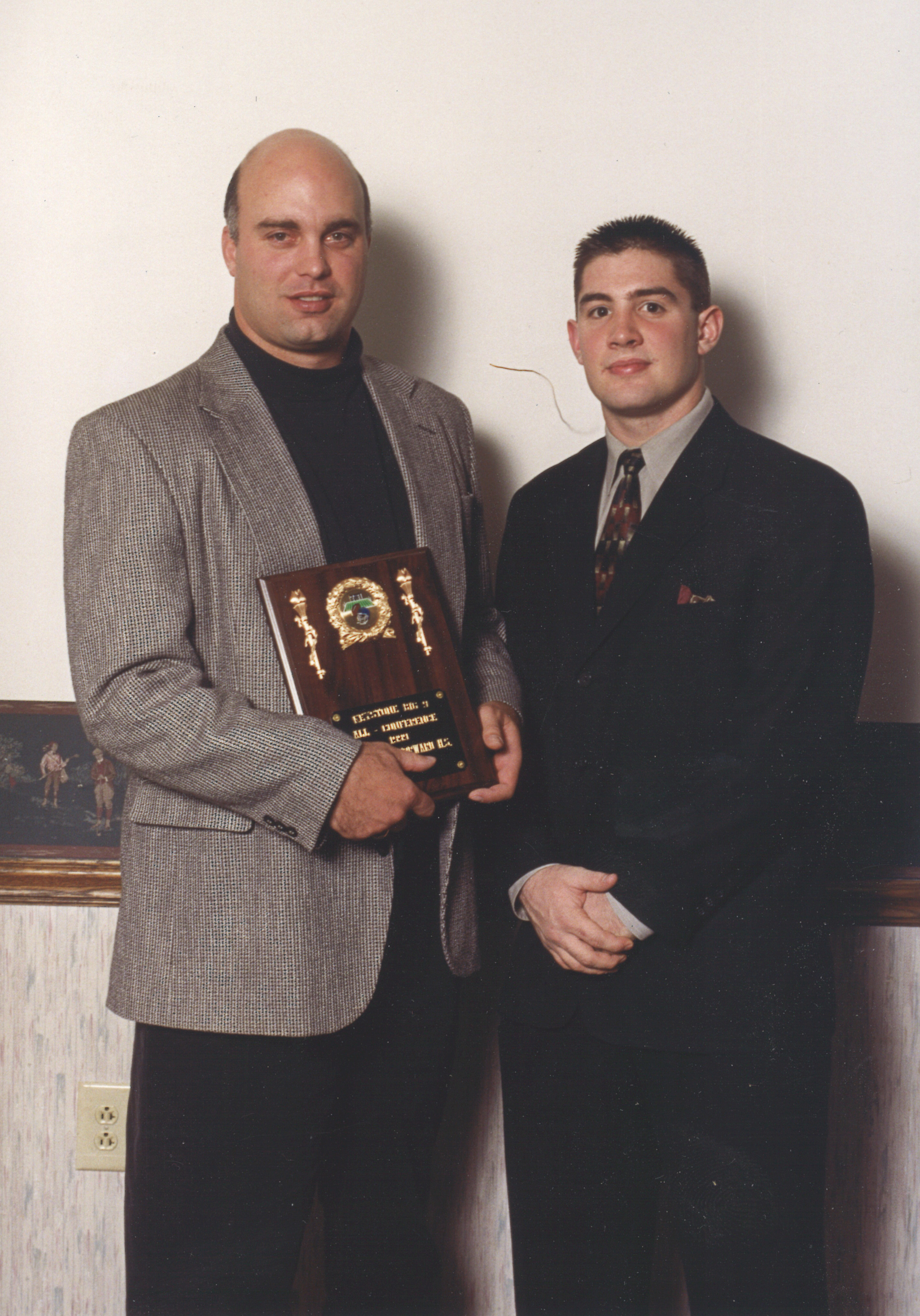

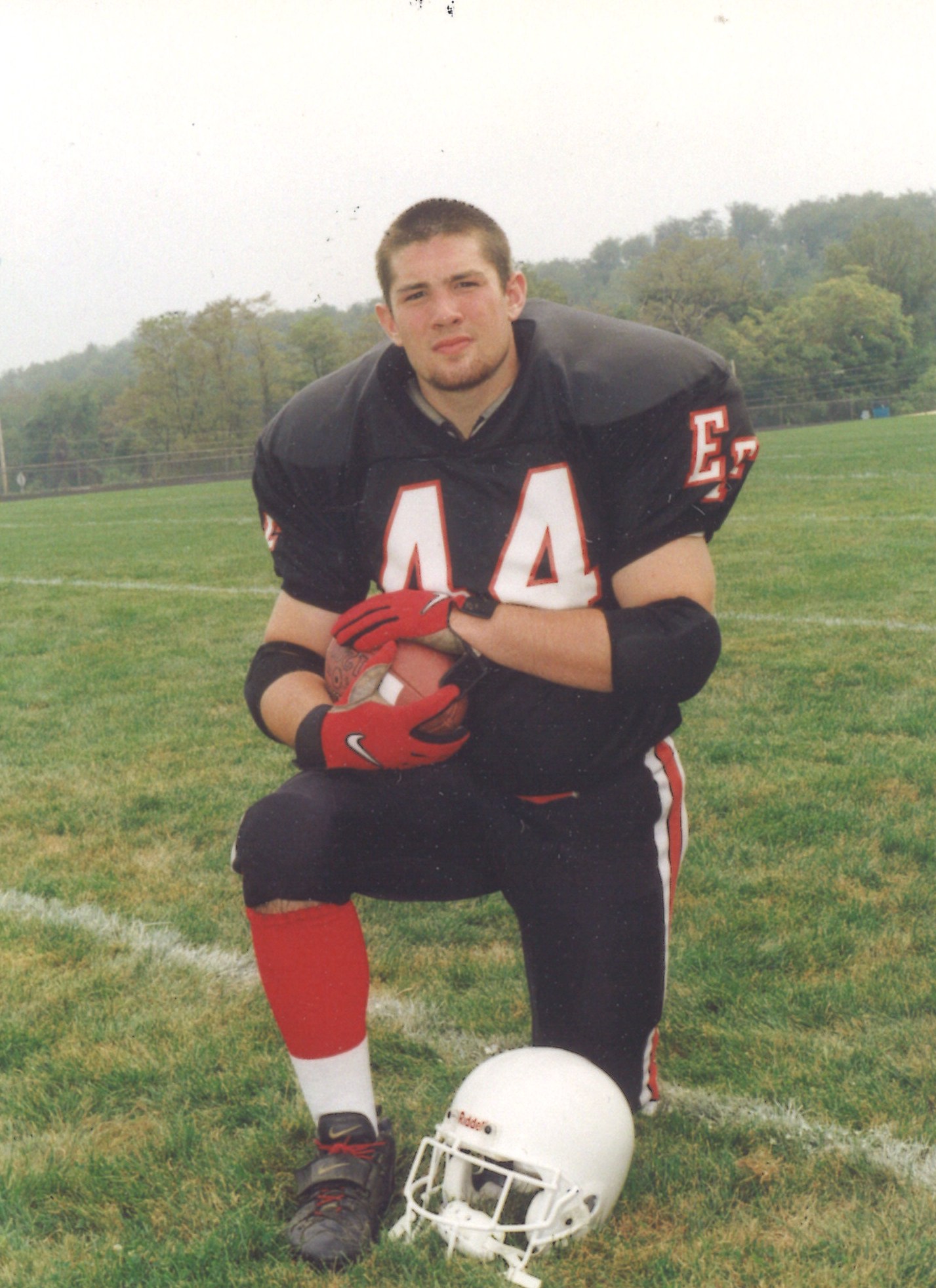

Every year we try to come up with a new message that might finally hit home with parents of young children, that “golden campaign” that would make parents realize their family is not immune. We know how easy it is for a normal kid to get CTE because our Patrick was not an NFL-type athlete. He was even too small for the elite college football teams, even though he made the Post-Gazette “Fabulous 22” list in 1998 and 1999. He was just a tough, brave, young man from the Mon Valley, playing a game he loved and trying to please his team, his coaches, his town and his parents.

Patrick played in middle and high school for the Elizabeth-Forward Warriors, a nickname that captures the culture of tackle football but misses the terrible costs. He had tons of heart, carried the ball a lot and was hit countless times. And all those hits eventually triggered CTE in his brain. Years after his football days had ended, we watched helplessly while his personality changed and he became unrecognizable to those who loved him. Through it all, Patrick was never diagnosed with a concussion.

Groundbreaking study

Most people associate CTE, if they are aware of it at all, with professional athletes — boxers, NHL skaters, NFL players. But new research demonstrates that youth contact sports generate terrible amounts of brain trauma, with tragic consequences.

Last week, Boston University published a study that examined 152 brains of amateur contact sport athletes who had died between the ages of 13 and 29. Of those kids who died much too young, 41% had CTE pathology in their brains. Most had died from suicide and drug overdoses, both of which are associated with CTE.

CTE is not mysterious. The pathology is known to be caused by repetitive hitting. This important study, a powerful warning to parents, was broadcast or published by almost every news outlet in the country. No parent could possibly want their precious child’s brain to be damaged, permanently, by playing a game. And yet, inexplicably and infuriatingly, the call for action continues to go unheeded. We ask ourselves, why?

Hear no evil, see no evil

Could it be optimism bias — that understanding of a danger in theory, but combined with the assumption that it could never actually happen to our family, to our child? For instance, we all know children can be paralyzed from a bad hit in football, but, because it’s very rare, parents are optimistic it won’t happen to their children. We certainly were. We let Patrick play football, aware of that slight risk. Maybe parents think that, like the risk of being paralyzed, CTE is rare?

The Boston University study should put that notion to rest forever. Among the brains the university has collected from the general population, only 1% show CTE pathology. Compare that to the 41% of collision-sport athletes who died before the age of 30. Assuming it won’t happen to your child isn’t optimism; it’s detachment from reality. CTE is anything but rare.

But the responsibility doesn’t only rest with parents. Schools are supposed to enriching the brains of the students in their care. Years ago, when we distributed leaflets about CTE at Elizabeth-Forward High School, security chased us off the property while leaders of the athletic association jeered at us. Schools know — and if they don’t know, it’s because they’ve chosen to ignore — the risks of repeated head trauma. Are athletic bragging rights and ticket sales worth it?

At the very least, will schools warn parents about the dangers of repetitive traumas to the brain so parents can make informed decisions? Will they stop allowing players to hit each other in practice, and to play both ways to minimize risk? Will they be courageous leaders and start a flag team instead? All schools should ask themselves these hard, important questions before another child’s brain is permanently scarred.

One brain, one chance

We are each endowed with only one brain. It is our most complex, spectacular and fragile organ, and a key part of what it means to be human. It cannot be replaced and it is very difficult, if not impossible, to repair. An injury to a young, still-developing brain alters everything about that person, that tender life, forever.

Parents, please, listen. We only get one chance at this. We thought we were doing the right thing by letting our Patrick play tackle football. We were terribly wrong and uninformed. and we will suffer with the knowledge of his agonizing suffering always.

Every parent teaches their children this basic lesson: “Just because everyone else is doing it, doesn’t mean you should.” It’s time for parents — and schools — to listen to their own advice. CTE is completely preventable. We all just need the courage to do it.

Karen and Doug Zegel are the founders of the Patrick Risha CTE Awareness Foundation.