Pitt legend knocked down racial walls at Sugar Bowl

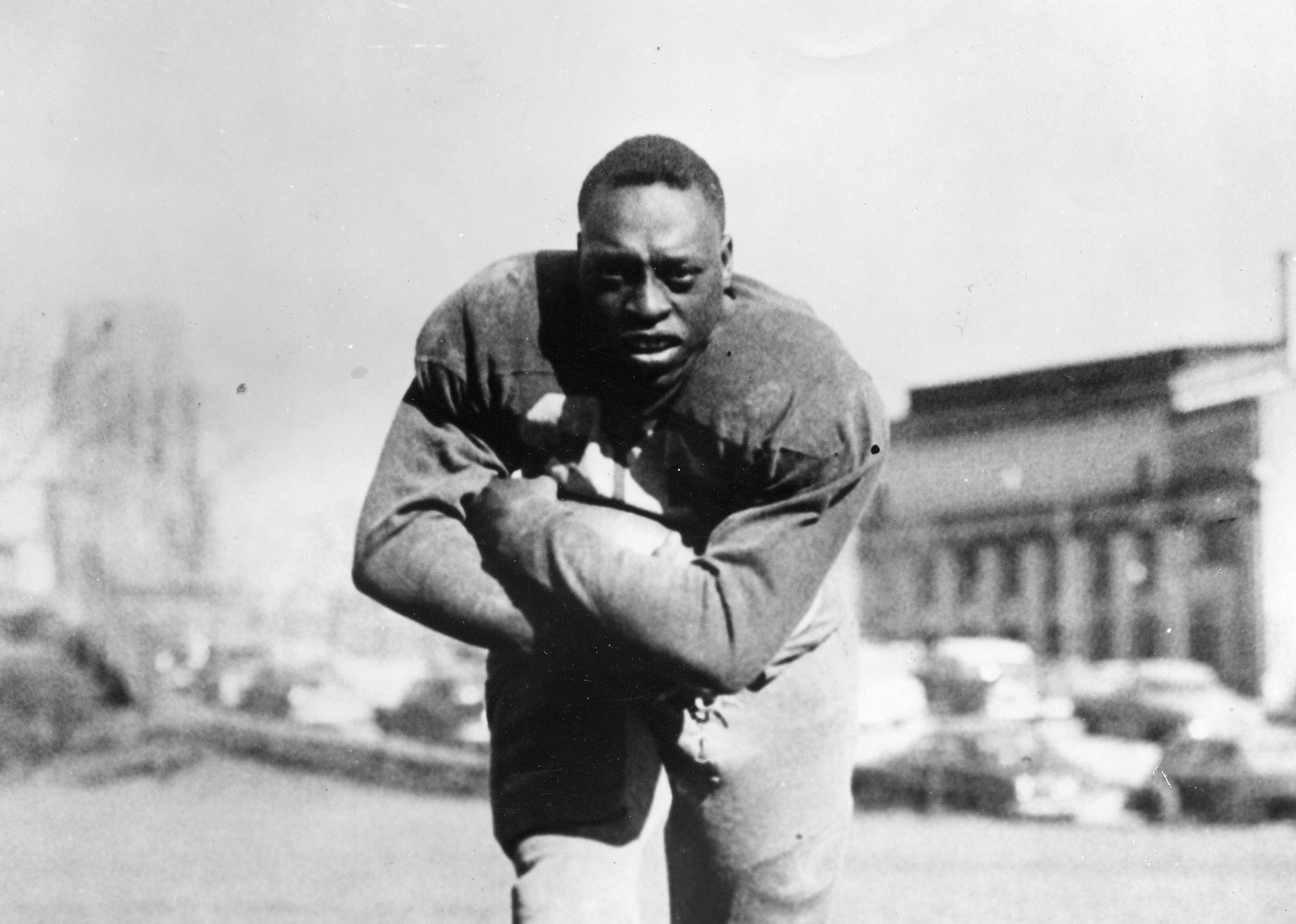

Bobby Grier didn’t like to stand in the spotlight that his career as a trailblazing athlete created. Even after withstanding racism and becoming a central figure in the fight for Black civil rights, he was never one to make a show of himself.

Grier was held back because of his race but didn’t harbor any bitterness for it. He was a national celebrity because of his courage, but rejected fame. He had already accomplished so much while so young but still kept pushing to be the best athlete, soldier, worker and father he could possibly be. The insatiable determination to better himself and his family shined above his place in the history books to those who knew him.

“What I know from my dad is love. He wasn’t about the fame,” Grier’s daughter, Cassandra, told the Post-Gazette. “He was just about being a good dad, and he’s a beautiful person. He would always give back. He was just a giving man.”

Pitt athletics lost a giant the morning of June 30, when Grier died at 91 years old at the Warren Nursing and Rehab Center in Warren, Ohio. The first Black player to compete in a Sugar Bowl, one of college football’s most prestigious postseason games, Grier defied racism in one of its American strongholds, served as a captain in the United States Air Force and cemented his place as an icon in University of Pittsburgh history.

Grier, a native of Massillon, Ohio, was a fantastic linebacker and fullback for the 1955 Panthers, who ended the regular season ranked No. 11 nationally and earned an invitation to take on No. 7 Georgia Tech in New Orleans’ Sugar Bowl the following January. Pitt accepted the invitation on two conditions — Grier must be allowed to play, and the sections set aside for Panthers fans in the traditionally segregated stands at Tulane Stadium must be integrated. The rallying cry became, “No Grier, no game.” Sugar Bowl officials and the Georgia Tech team both accepted.

But Georgia Gov. Marvin Griffin, a staunch segregationist, demanded the Yellow Jackets forfeit the game and honor the decades-long-standing “gentleman’s agreement” that compelled segregated schools to turn down offers to play against integrated teams.

“The South stands at Armageddon. The battle is joined,” Griffin told reporters in the lead-up to the game. “We cannot make the slightest concession to the enemy in the dark and lamentable hour of struggle. There is no more difference in compromising integrity of race on the playing field than in doing so in the classrooms. One break in the dike and the relentless enemy will rush in and destroy us.”

His maneuver was miscalculated. Griffin backed down in the face of student protests mounting on campus at Pitt (which were backed by then-acting chancellor Charles Nutting), Georgia Tech, Mercer University, Emory University and the University of Georgia, with more public pressure flooding in from around the country. Preparations for the Sugar Bowl proceeded, with Grier included, but the widespread acceptance didn’t insulate Grier from racism as the team traveled to New Orleans.

All the public support Grier received was dwarfed by the serious, deadly threats racism in the deep south still posed to Black Americans.

In the summer of 1955, Emmett Till was brutally lynched in Mississippi, and less than a month before the 1956 Sugar Bowl, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up the seat she had paid for on a public bus in Montgomery, Ala. Jim Crow Laws had been challenged but were far from collapsing.

Grier was not allowed to stay in a room at the whites-only hotel in New Orleans his teammates occupied, and he relocated to more welcoming neighborhoods populated by Black people who accepted him with open arms and hot meals.

He was isolated from his teammates but far from alone.

“He said he would stay in the neighborhoods with [some of the Black high school and college] coaches and he would get fed very well by the neighbors and some of the women in the neighborhood and the wives of some of the coaches there,” recalled his sister-in-law, Barbara Williams Pridgen. “Good, home-cooked meals — fried chicken, sweet potato pie, apple pie, peach cobbler — the kind of good southern food that the boys at the hotel weren’t able to get.”

While he became a national celebrity for his effort to play in the Sugar Bowl, Grier was denied entry to several team events on the basis of his skin color. Still, the Georgia Tech and Pitt teams wielded whatever influence they could to make Grier feel welcome at fraternity parties on campus at Tulane and even at the infamously segregated St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans.

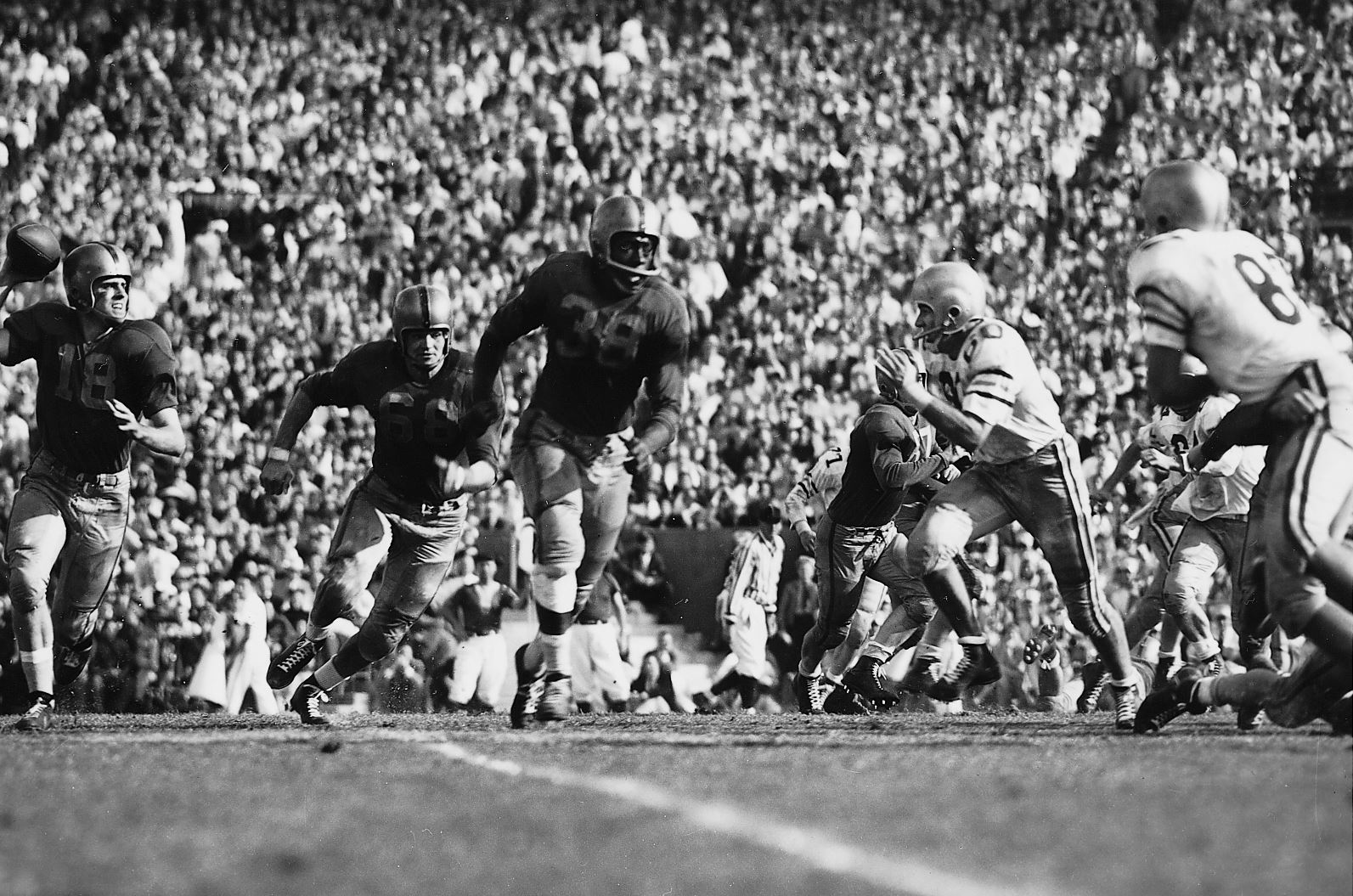

Pitt lost the 1956 Sugar Bowl, 7-0, due in large part to controversial pass-interference penalty — one that referee Frank Lowry later admitted was the wrong call — leveled against Grier in the first quarter, which resulted in the game-winning touchdown for the Yellow Jackets. Grier insisted until his death that it was a rotten call.

Despite the hatred he faced and the isolation from his teammates, Grier’s lasting memories of the 1956 Sugar Bowl were positive and gracious. He constantly lauded the clean play of the Yellow Jackets, their acceptance off the field, and the support of his own team and classmates back in Pittsburgh.

“He was a groundbreaking player in the segregated south and the people he met, and the experiences that he had gave him the ability to keep his head on straight,” Pridgen said. “He was never bitter or angry about anything he went through. I don’t know how he was able to do that.”

His already rich life became even richer in his adopted city of Pittsburgh, where Grier went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in business from Pitt in 1957 then enjoy long careers with U.S. Steel and the Community College of Allegheny County following his military service with the Air Force as a missile and radar supervisor.

Grier and his wife, Dorothy, a Pitt alumna, were able to send kids to Sewickley Academy, a private prep school just outside of Pittsburgh. Like Grier at Pitt in the 1950s, Cassandra and her brother Rob were two of the few Black people who lived in their hometown. Grier coached their sports teams and pushed them academically, reinforcing them with the strength he used to overcome his own experiences as a Black person in a mostly white world.

“Because he was such a pioneer and persevered, he helped us to be strong in that situation,” Cassandra said. “He basically instilled in us a strength because he has it.”

As he grew older, Grier and his family became active participants in the Elizabeth Dole Foundation, which supports military caregivers — spouses, parents, family members, and friends who care for America’s wounded, ill, or injured veterans.

The African American Alumni Council of the Pitt Alumni Association bestowed upon him its Distinguished Alumnus Award in 2017. The Sugar Bowl welcomed him into its own Hall of Fame in 2018. And he was officially inducted into the Pitt Athletics Hall of Fame in 2022.

Bobby Grier was talented, determined and courageous, and his appearance in the Sugar Bowl, despite its bitter end, represents a pivotal moment in the American civil rights movement. But to his family, Grier was a loving father, generous servant to his community and a strong man before any of the accolades that decorate his biography.

“He was an African-American man who defied the odds and did it with grace and beauty and class,” Cassandra said. “He had a life beyond football. He was a beautiful man beyond football. He was a tapestry. He wasn’t just one-dimensional.”

Stephen Thompson: sthompson@post-gazette.com and @stephenethom on X