major game changer

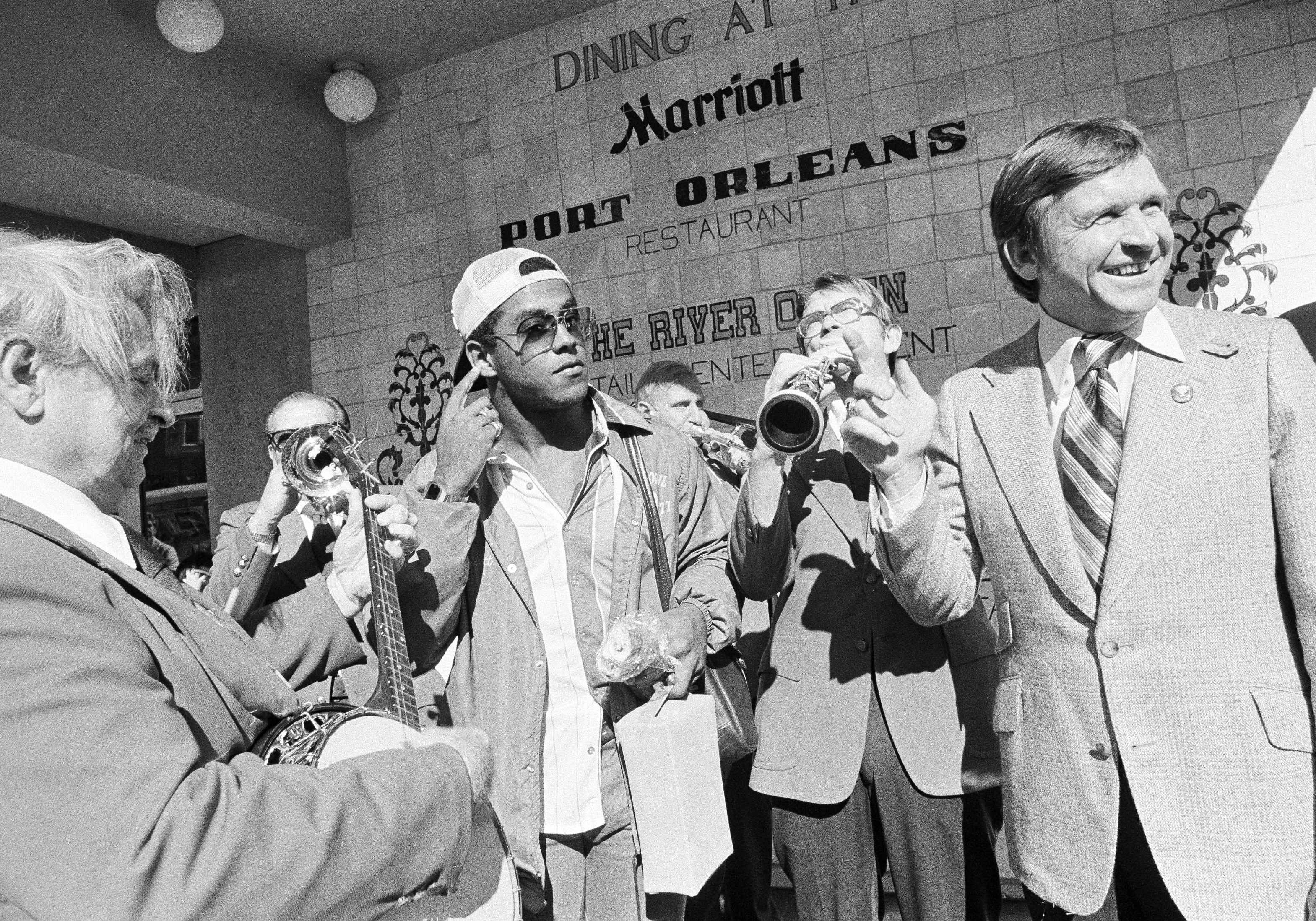

When Pitt coach Johnny Majors took over in 1973, he signed a freshman class of 67 players. There were no scholarship limitations, so his strategy of loading up on talent helped to develop a perennial top-10 program — culminating in a 1976 national championship.

Five decades after the NCAA responded to the Pittsburgh coach’s tactics by instituting the “Majors Rule” — a football scholarship cap that opened a period of relative parity among schools with sometimes wildly different budgets — another massive step toward the modernization of college athletics is on the NCAA’s doorstep.

A settlement expected Monday in a case known as House v. NCAA will allow Division I institutions to compensate student-athletes directly for the use of their names, images and likenesses; establish a $2.8 billion fund for back pay to former athletes; and require that schools pay tens of millions of dollars annually to their competing athletes on scholarship.

U.S. District Judge Claudia Wilken in Oakland, Calif., is expected to usher college athletics into a brave new world when she considers final approval of the settlement that will resolve Grant House and Sedona Prince v. National Collegiate Athletics Association, et al.

No part of Division I athletics would be left untouched. But, despite the advancement of decadeslong pay-for-play debates, many pressing questions will remain.

The NCAA’s member institutions would still need to find answers to determining employment status and collective bargaining rights for athletes, satisfying Title IX requirements and deciding which ‘non-revenue’ sports programs must be cut to clear budgets for the added costs of player compensation. Maintaining a competitive landscape also remains a core issue.

Every school will have its own distinct hurdles to clear.

Pitt, Penn State and West Virginia, all with limited operating budgets, must free up tens of millions of dollars to accommodate new revenue-sharing regulations and cover 10 years of back pay to athletes.

Mid-major schools like Duquesne and RMU now stare down an even more uneven playing field due to the settlement’s removal of scholarship limits and the ever-expanding transfer portal landscape.

Even smaller schools like Saint Francis University — a Cinderella in this year’s NCAA basketball tournament — face questions about whether remaining in Division I is sustainable.

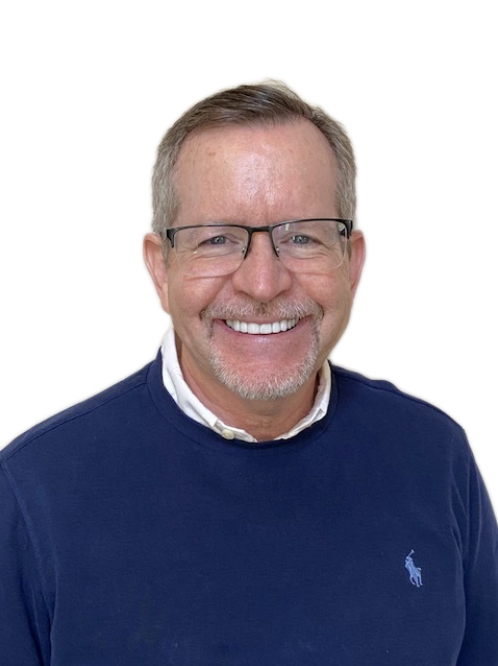

“We have to evolve,” Pitt Athletic Director Allen Greene said in an interview with the Post-Gazette last week. “This is not the athletics department of three years ago or four years ago and let alone of 20 years ago.”

House v. NCAA’s ripple effects also will trickle down to individual athletes and celebrity-like brands such as LSU’s Livvy Dunne — a prized Olympic gymnast and social media star — who are concerned about being shortchanged by the settlement’s terms.

Monday’s ruling in the “House Settlement” will not only be the culmination of five years of litigation. It will also give birth to a new era of college athletics that many see as a major victory in the decadeslong fight between the NCAA’s governance of amateurism and paying athletes what’s rightfully owed to them.

And it all starts with writing checks for back pay for lost earnings.

Billions in back pay

The decision to settle was influenced by concerns over potential bankruptcy. Had the case proceeded to trial, the NCAA would have faced exposure to damages of up to $20 billion.

Although Monday will not mark the House Settlement’s final day in court — more litigation is expected, and enacting the actual terms will take time — it has been a long time coming.

In 2009, former UCLA basketball star Ed O’Bannon led a class-action lawsuit that won $42.2 million in damages after his likeness — and that of other athletes — was used without his consent in college sports video games. Electronic Arts and the NCAA discontinued that video game series for over a decade rather than pay athletes.

In Monday’s proposed settlement of the House case, the two parties have agreed that $2.78 billion will be paid to athletes who competed from 2016 through Sept. 14, 2024, to make up for missed earnings opportunities due to pre-2021 restrictions.

An estimated 390,000 athletes are eligible for some of that money, and payments will be scheduled to go out over the next 10 years — $280 million annually.

The $2.78 billion will not be evenly distributed.

About 95% of back pay is expected to reach the pockets of players from the settlement’s five defendant conferences — the Big Ten, Big 12, SEC, ACC and Pac-12, also known as the ‘power conferences’ in this case, in addition to the University of Notre Dame. A breakdown of 75% is expected to go to football players, 15% to men’s basketball players and 5% to women’s basketball players.

The NCAA’s other 27 non-power conference schools have a major issue with this plan, as they’re expected to provide nearly 60% of the money ($990 million), compared to 40% ($664 million) from the power conference schools that generate much more revenue.

Duquesne University, for one, has been vocal about its frustration.

“Much of the burden of the House settlement is being placed on colleges and universities that really didn’t create the problem in the first place — and whose athletes and graduates will not get the benefit of most of the House Settlement,” President Ken Gormley said in an interview with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

“It’s upside down. It’s unfair. And that has troubled me from the start.”

It also doesn’t help the Dukes that Division I conferences will lose future revenue from the March Madness tournament due to the $2.78 billion in back pay — the NCAA pays its conferences roughly $2 million for every game played in its prized postseason basketball tournament.

This could devastate the nearly 280 non-power conference schools comprising roughly 80% of all Division I institutions. Many of these conferences typically only send one team to the NCAA tournament every March and rarely receive more than one or two games’ worth of this revenue.

The SEC — which had a record-breaking 14 teams make the Big Dance in 2025 — is expected to receive close to a $70 million payout after Monday night’s national basketball title game.

A lack of parity extends to the gridiron, too.

The current “Power Four” conferences alone (excluding the Pac-12, which is no longer considered a power conference) are set to receive 90% of revenues from the expanded College Football Playoff setup, an event managed independently from the NCAA that will generate more than $1.4 billion annually.

And, despite comprising nearly 93.5% of all Division I athletic programs, athletes from the NCAA’s 43 so-called ‘non-revenue’ sports will receive just 5% of the $2.78 billion in back pay.

Title IX, a 1972 federal civil rights law that requires schools to allocate equal opportunities (scholarships, funding and facilities) to men’s and women’s sports programs, remains a core issue. The initial settlement proposal complied with Title IX, though a later adjustment removed a clause requiring equal revenue distribution among men’s and women’s sports.

The average damages award for a power conference football player or men’s basketball player is projected to be about $135,000 over the next 10 years.

Women’s basketball players are expected to be paid an average of $35,000, though few schools have publicly stated how they plan to divide the pot.

The exact amount issued to each player will be based on a combination of factors, including the athlete’s sport, the conference they played in and their playing time — with years played and minutes on the court or field factored in.

Name, image and likeness

There’s a reason for the disparity in payments: Football and men’s basketball players have more opportunities to cash in commercially on their names, images and likenesses than athletes in other sports.

About $1.98 billion of the back pay is being set aside to cover missed opportunities in broadcast outlets, video games and anything else deemed a “lost NIL opportunity.”

There aren’t video games for women’s volleyball, men’s soccer or the NCAA’s other non-revenue sports — including Olympic athletes — and the broadcast viewership for those sports is not as gaudy.

Ms. Dunne, currently one of Division I’s highest-paid athletes, has millions of social media followers and has parlayed that into branding deals with Nautica, South Side-based retailer American Eagle Outfitters and more. Her NIL valuation has been estimated as high as $4 million.

Though she is a bona fide celebrity in the world of college athletics, she still will be lumped in with the 5% of non-revenue athletes in the settlement.

And she’s not alone.

Ms. Dunne represents one of the 343 athletes who had opted out of the settlement as of March, and she will be one of 14 objectors at Monday’s hearing in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, which is scheduled to start at 1 p.m. EST.

In a letter dated Jan. 31, Ms. Dunne claimed that the House v. NCAA settlement fails to account for the full breadth of lost NIL earnings to which an athlete could be entitled. Her letter is one of 73 formal objections submitted to the court from more than 35 filings.

“If I were to hire a law firm to represent me individually in this matter, I would want to know how the valuation of damages was calculated specifically to me,” Ms. Dunne wrote.

Former Pitt volleyball players — such as Julianna Dalton, who has 104,000 followers on TikTok, or Cat Flood, with 50,400 followers — might be worth well more than the formula for back pay outlined in the settlement. Because of this, Ms. Dunne and other opponents of the settlement fear money is being left on the table.

Pitt’s volleyball team has gone to the Final Four competition the past four years, and Olivia Babcock was named National Player of the Year in December. How would Pitt evaluate Ms. Babcock and her teammates for back pay? Volleyball generates the fourth-highest revenue of any of Pitt’s varsity teams, but even that comes out to a little more than half of what women’s basketball brings in annually.

Former Penn State wrestler Bo Nickal graduated before the era of name, image and likeness began and won three individual national championships while helping to lead the Nittany Lions to four consecutive team titles from 2016-19. He was a fan favorite during his time in Happy Valley and amassed a large social media following, but he will likely receive minimal back pay.

Penn State’s wrestling program, under head coach Cael Sanderson, has claimed 12 of the NCAA’s last 14 national titles, creating one of the greatest dynasties in college athletics. Though the Nittany Lions seem committed to investing in future wrestling success, other programs across the country are prime candidates to be cut to make room for paying the more than 190,000 current NCAA Division I athletes.

“I always tell Cael, we’re going to do whatever we need to do to give you all you need, the resources you need. … I can tell you that we added scholarships for him in the future,” Penn State’s vice president for intercollegiate athletics, Pat Kraft, said at a news conference Feb. 24.

McNeese State student manager Amir Khan is a prime example of how social media fame can become cold, hard cash in the world of NIL. He became a viral sensation in March for his boom box-driven musical inspirational tactics during the Cowboys’ run through the Southland Conference and NCAA basketball tournaments, and he signed sponsorship deals with Buffalo Wild Wings and Insomnia Cookies as a result.

Critics like Ms. Dunne are skeptical that the House settlement’s back pay formula could account for those kinds of opportunities that sometimes appear out of thin air.

Revenue sharing

While Monday’s settlement hearing results would allow Division I schools to pay their athletes directly, critics point to a per-school payment cap that they see as simply replacing one illegal restriction with another.

The House Settlement allows each school to share “up to” $20.5 million per year with its athletes starting in the 2025-26 season, which represents 22% of the “average media rights, ticket sales and sponsorship revenue of each power conference school.”

The wording here is important, though, because schools could still choose to share less than that despite it hurting their chances to remain competitive in recruiting top-tier talent.

And while power conference schools generate an average of about $100 million in annual revenue, many will still lack the surplus necessary to pay athletes and maintain a profit.

In its latest Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act filing, Pitt reported $138.64 million in total revenue during fiscal year 2023-2024, an increase of nearly $2 million from the year prior.

That figure includes $49.48 million from football and $20.21 million from men’s and women’s basketball.

But, like all but a few college athletic departments in the NCAA, Pitt reports that it operates without turning a profit. It reported $138.64 million in expenses, putting it at the break-even point during the last fiscal year.

And on top of the tens of millions of dollars that will need to be paid out to satisfy the House Settlement, Pitt is in the middle of a massive athletics capital project — the $240 million “Victory Heights” facility being built adjacent to Petersen Events Center in Oakland.

Mr. Greene, who was appointed Pitt athletic director in October, said the university is still in discussions to determine how money will be allocated to account for its $240 million Victory Heights project, revenue sharing and NIL costs.

Pitt athletics, which is drawing from multiple sources to address the revenue-sharing demands of the House Settlement, will also rely on institutional support. The university views its programs — especially the highly visible football and men’s basketball teams — as worthwhile investments for Pitt at large.

“The banner programs … football and men’s basketball, those get the most eyeballs, and we have revenue opportunities tied to those two programs in particular,” Mr. Greene said. “It’s important for us to draw from those revenue opportunities along with the community and our donors through philanthropic help and through institutional assistance to help put us in position for us to have success.”

The Panthers’ power-conference counterpart in Pennsylvania, Penn State, reported $220.76 million in total revenue for its athletic department in 2023-24.

But even the Nittany Lions — who boast one of the nation’s highest athletic department revenues — will need to make adjustments to account for the extra money being diverted to players in 2025 and beyond.

“We don’t have a $20 million surplus every year in our athletic department,” said Jay Paterno, son of legendary Penn State football coach Joe Paterno. Jay Paterno is a member of the university’s board of trustees and a co-founder of the Success With Honor NIL collective.

“Where does that $20 million come from? That’s going to be the biggest question.”

The aftermath of the House Settlement will also intensify the emphasis on broadcast deals to help pay athletes at higher-profile schools.

And it won’t stop there.

“You can have naming rights to the field. You can have naming rights to the lights over the stadium. Everything’s for sale,” said John Affleck, head of Penn State’s journalism department and director of the school’s John Curley Center for Sports Journalism. “It just becomes a little bit more transactional, perhaps a less intensely emotional experience.”

Scholarship limits

The House Settlement also would eliminate scholarship limits in all sports. Schools would have to decide how many scholarships they want to use, with no rules or requirements on granting full scholarships to athletes from specific sports programs.

Roster caps would be aimed at preventing power schools with deep pockets from hoarding talent and widening the gap with smaller programs, according to the NCAA.

Power conference teams, however, have a history of hoarding top talent, making it difficult for the NCAA to maintain a competitive balance across its Division I programs.

Back when Johnny Majors took over the Panthers’ football program in the early 1970s, his massive freshman class signings did not make rivals happy, and Pitt’s recruiting dominance during this time is considered one of the reasons NCAA football caps were initially set at 95 scholarships in 1977.

With legal fees from the House Settlement expected to exceed $750 million, power conference schools have already projected sweeping increases — including ticket price hikes — to cover the cost of issuing new scholarships starting in the 2025-2026 season.

The transition from scholarship limits to roster caps in 2025-26 is expected to significantly affect non-revenue sports and walk-on athletes, potentially reducing opportunities for those players and disproportionately reallocating resources within athletic programs of all sizes.

Matt Brown, founder and publisher of the Extra Points newsletter, which covers business and policy news in college sports, says non-revenue college sports like baseball will need NIL revenue to survive, even at power conference schools like Penn State.

“I wouldn’t be shocked if the (Penn State) baseball budget was $0 even though there’s going to be teams in the Big Ten whose baseball budget will be in the seven figures,” Mr. Brown said. “They’re still going to pay the scholarships, but if you want any money on top of that, that would need to come from marketing deals that players themselves secured.”

Proponents of roster caps say it’s a more legally defensible way to regulate rosters without directly limiting player compensation.

Critics point to hypocrisy, though, as athletes are still not considered employees under the terms of the settlement and are not entitled to collective bargaining. The U.S. Department of Justice has taken a hard stance on this topic.

With schools having free rein over how they allot scholarships, smaller sports that don’t generate revenue may simply see a reduction in funding — or be cut altogether.

Critics claim the strict nature of new roster-size limits could eliminate hundreds — if not thousands — of scholarships, disproportionately affecting non-revenue sports (Olympic sports included) and female athletes while raising significant Title IX concerns.

Mid-major impact

Individual program cuts aside, it’s the smaller institutions that could suffer the most from the House Settlement’s call to remove scholarship limits.

Mid-major programs, also known as the NCAA’s non-power conference schools, have benefited in the past from scholarship limits because top recruits often don’t want to sit on the bench without a scholarship at a power conference program. A skilled athlete might choose to attend schools like Duquesne and Robert Morris because they’d get more playing time plus a scholarship.

Sporting News college basketball columnist Michael DeCourcy believes mid-majors must sell the idea of immediate playing time now more than ever.

“If you come here, you’re going to play right away, and you’re going to matter. If you play here for a couple of years and do well, and somebody comes along and offers you a couple [million], hey, we helped get you there,” said Mr. DeCourcy, who covered sports for The Pittsburgh Press from 1983 to 1993 and has spent much of his career since then examining the national landscape of collegiate athletics.

Some mid-major programs simply don’t want to be considered feeder teams, and it’s one of the main reasons Saint Francis announced its move from Division I last month.

Just two weeks after the men’s basketball team’s March Madness appearance, Saint Francis announced that the Red Flash would be joining the Division III Presidents’ Athletic Conference. Men’s basketball coach Rob Krimmel announced his retirement two days later.

In an in interview with the Post-Gazette, St. Francis’ president, the Rev. Malachi Van Tassell, said the school was forced to reconsider its future due to the “liberalization of the transfer portal” and its “inability to compete with the name, image and likeness scheme.” The university’s athletics programs will reclassify for the 2026-27 academic year.

Other schools will likely follow in the Red Flash’s footsteps, according to Mr. Brown, because the NCAA doesn’t allow athletic scholarships at the Division III level.

“Then it makes it easier to say, ‘If we just move to Division III, we cut back on our travel, we don’t have to worry about [paying out athletic scholarships],’ ” Mr. Brown said.

Uncertainty ahead

The NCAA’s rapidly evolving transfer portal, which officially began in 2018, has already made the success of mid-major basketball programs harder to sustain.

Robert Morris’ entire starting lineup is in the transfer portal after making the NCAA tournament. Horizon League Defensive Player of the Year Amarion Dickerson also has interest from close to 20 power conference schools — including Pitt.

Men’s basketball coach Andy Toole, who recently signed a contract extension with RMU, has also voiced his concerns about the portal system. In early March, he said he was having to balance paying attention to the portal before the Colonials even made it to the Horizon League finals.

As of late March, five West Virginia University men’s basketball players — including four starters — had entered the NCAA transfer portal. Pitt is down to just four scholarship players left on its squad. Duquesne lost its leading scorer and two other scholarship players.

And that’s just the transfer portal chaos before the new rulings from House v. NCAA.

While the 27 non-power conferences and their schools can opt out of the proposed House Settlement — as the Ivy League has announced it would do — they can’t opt out of the damage done by the unpredictable and often brutal realities of the transfer portal landscape.

Duquesne has already said it will opt in, but the decision doesn’t come without concerns.

“We have a long history of being competitive in men’s basketball and women’s basketball and other programs that we intend to remain competitive, but that doesn’t mean that there should be no check on how the NCAA is structuring these changes,” said Mr. Gormley, the university president.

“We’ll keep a careful eye on it in the upcoming years, and I’m hopeful that — as it becomes clear that the current structure is not particularly fair to the bulk of universities and colleges in the United States — the NCAA will make adjustments to place more emphasis on the fact that this is really about creating student-athletes and having student-athletes have a wonderful experience.”

Staff writer Maddie Aiken contributed to this report, along with Joel Haas, a student at Penn State University, and Ava Dzurenda, a student at Saint Francis University and a member of the university’s cross country team.